Tysk pilot fanges

Fortalt af: William M. Fry

Mistede endnu en i dag, Tod. Havde kun været her en uge eller to. I messen er nerverne på højkant, uheld er altid deprimerende.

Før offensiven skal jagerenhederne garantere beskyttelse af vores skjulte angrebsenheder på jorden samt beskytte vores rekognosceringsfly.

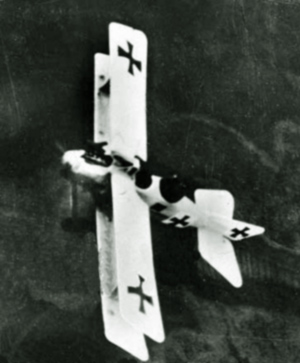

Den tyske pilot med flest nedskydninger under 1. Verdenskrig.

Off we go into the wild blue yonder,

Climbing high into the sun;

Climbing high into the sun;

Jeg kan høre flyvere i natten

Er det fjende eller ven

Er det nu det sker

Er det nu de kommer igen

Er det fjende eller ven

Er det nu det sker

Er det nu de kommer igen

It was the ambition of every young pilot to bring down a German on our side of the lines. This particular pilot, however, with me on his tail and aware that he had stirred up a hornet's nest by appearing over the aerodrome, decided to land and did so very fast on an open space, turning over on his back.

In the excitement of following so close on his tail, I had no idea of the height we had lost and that we were so near the ground and nearly flew into it on top of him, pulling upward only just in time when I saw his machine tip up in front of me. I landed close by and shook hands with the pilot who admitted that he had lost his way. The usual crowd of soldiers appeared from nowhere and all were from a battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry in which I was commissioned and whose badges I was [still] wearing. They were in rest [briefly out of the line] nearby. The adjutant got me put through to Major Scott on the telephone and he arranged to send his motor-car out at once for the German pilot and also a salvage party to collect his machine. l flew back to the aerodrome.

The CO instructed the salvage party to dismantle and bring the German plane in as soon as possible as General Trenchard was expected on a visit the next day and he wanted to show him the machine. I seem to remember that the GOC took little interest, but the technical staff who came out later discovered that it was an improved and previously unknown type of Albatros and it was sent straight off to England for inspection.

It was the custom for RFC squadrons to entertain pilots and observers whom they had brought down alive, before handing them over to the prisoner of war cages for interrogation. The Germans did the same. So my German pilot was brought in to luncheon and plied with drink on the chance that we might get some interesting information out of him. He did not say much and gave nothing away, but we did find in his tunic pocket a ticket for Cambrai theatre for the night before. He was Leutnant Georg Noth of the Boelcke Jasta. The whole affair was no achievement on my part as it was pure luck to come across him over the clouds, there was no fight and once I got on his tail he gave up.